Metropolis Magazine: What I Learned About Experience Design From Buckminster Fuller

Posted August 1, 2018

Edwin Schlossberg, President and Principal Designer of ESI Design, shares in Metropolis Magazine how his directorship of Fuller’s World Game continues to shape his work in experience design:

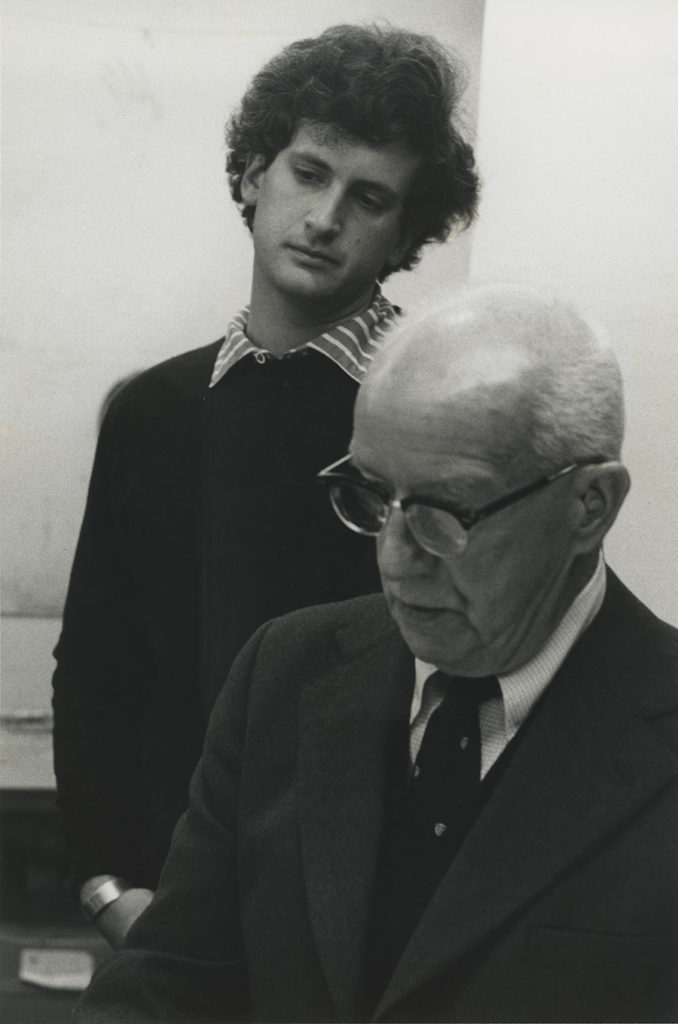

I had the good fortune to meet Buckminster Fuller, the architect who designed the geodesic dome and championed sustainable design before there was even a term for it, when I was in my early twenties. At the time, I was fascinated by the intersection of art, design, and technology but was not sure as to how to turn that into a professional career. Fuller was developing his World Game, an ahead-of-its-time simulation that allows a group of people to collaborate on addressing the world’s problems. At a time of increasing globalization, it was a revolutionary initiative to help world leaders work together to achieve universal goals like conservation, rather than each country hacking away at global issues piecemeal.

Fuller’s insight that the earth could be thought of as a single closed system whose inhabitants shared the same needs and objectives resonated with me. I was also impressed by his conviction that his ideas could improve the way humanity functioned and, in 1969, I leapt at the opportunity to serve as director of the World Game Workshop.

Over the course of about three months, I wrote the proposal that secured the project’s funding from the Rockefeller Foundation and IBM and I arranged for the World Game Workshop to be housed at the New York Studio School in Greenwich Village. I oversaw the search strategy to secure participants, interviewed and selected applicants, organized daily activities, and managed documentation of the project including filming and the creation of the final report. The experience advanced my own thinking, igniting a lifelong appreciation for games as a means to bring people together to solve problems.

However, metaphorically speaking, while Fuller was fantastic at writing menus, and sometimes cooking, he didn’t care much to see the diners’ response to the meal. That’s where I differ. I have always been as interested in the audience—are they delighted, surprised, awed?—as I am in the experience.

My first design project was, in 1977, to reimagine the Brooklyn Children’s Museum. Working with the museum staff, my team developed one of the first “hands-on” museums in the world. Kids learned about their connection with the natural world by interacting not just with the exhibits but, more importantly, with each other. They could, for example, collectively power a water pump by running a windmill, or create songs on musical pipes using a giant wind machine. That same year, I started ESI Design with a project for the Massachusetts Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals’ Macomber Farm. The farm helped visitors develop empathy for animals through dozens of interactive activities, such as a pair of binocular-like head-sets that enabled them to see the world through the eyes of different animals like a cow (90-degree vision) or a sheep (in black and white).

Join The Conversation