Museums used to be passive experiences that presented artifacts behind glass. The Brooklyn Children’s Museum wanted to rethink this approach, and hired a young designer, Edwin Schlossberg, to do it.

Opportunity: Museums, including those for children, used to be passive experiences that presented artifacts behind glass. The Brooklyn Children’s Museum wanted to rethink what a children’s museum experience could be, and hired a young designer, Ed Schlossberg, to do it.

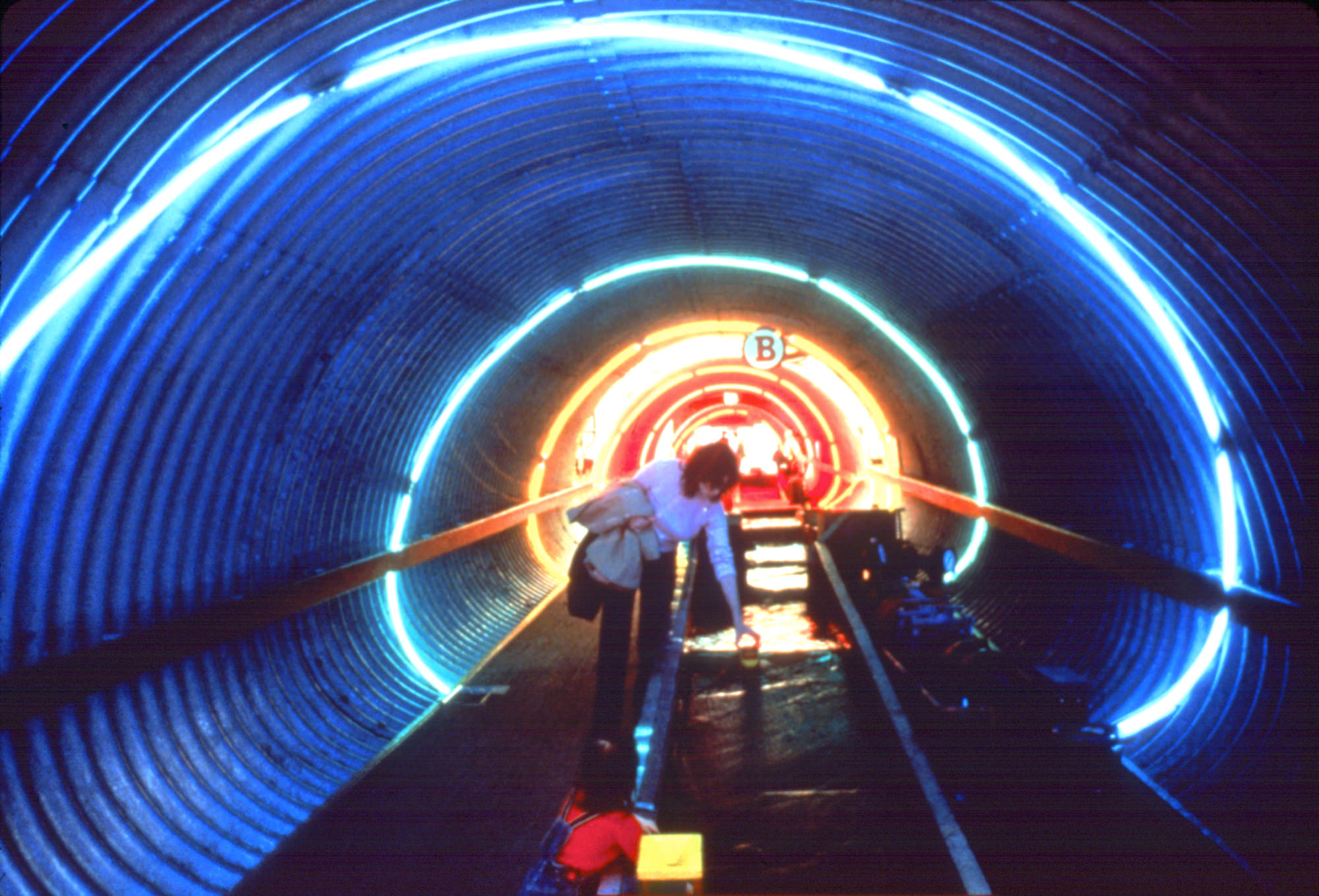

Solution: Ed created The Learning Environment, a participatory experience that invited children to explore the fundamentals of nature—earth, air, fire, and water-—in ways that ignited their natural curiosity and desire to participate. The hands-on exhibition was among the first of its kind: Instead of presenting information, it encouraged children to ask questions, learn by doing, and make their own connections. Visitors traveled through the space in a tunnel, which still exists in the museum today, with neon lights and a trench of flowing water that could be manipulated with sluices and locks and obstacles. Children learned about nature through stations created from recognizable objects, such as a playground based on the structure of a molecule. These touchpoints effectively infused the environment with experimentation and play.

Result: This award-winning and influential exhibit transformed what a museum experience could be and set the standard for interactive excellence, for ESI Design, and for the entire field.

"As museums go, the new Brooklyn Children's Museum doesn't exactly conform to type. You go in through an old‐fashioned trolley car kiosk, walk down a ramped culvert of corrugated steel called a 'people tube,' and find yourself in a Rube Goldberg fantasyland of contraptions that seem designed to make busy, happy children even of grown‐ups."

Museums used to be passive experiences that presented artifacts behind glass. The Brooklyn Children’s Museum wanted to rethink this approach, and hired a young designer, Edwin Schlossberg, to do it.

Opportunity: Museums, including those for children, used to be passive experiences that presented artifacts behind glass. The Brooklyn Children’s Museum wanted to rethink what a children’s museum experience could be, and hired a young designer, Ed Schlossberg, to do it.

Solution: Ed created The Learning Environment, a participatory experience that invited children to explore the fundamentals of nature—earth, air, fire, and water-—in ways that ignited their natural curiosity and desire to participate. The hands-on exhibition was among the first of its kind: Instead of presenting information, it encouraged children to ask questions, learn by doing, and make their own connections. Visitors traveled through the space in a tunnel, which still exists in the museum today, with neon lights and a trench of flowing water that could be manipulated with sluices and locks and obstacles. Children learned about nature through stations created from recognizable objects, such as a playground based on the structure of a molecule. These touchpoints effectively infused the environment with experimentation and play.

Result: This award-winning and influential exhibit transformed what a museum experience could be and set the standard for interactive excellence, for ESI Design, and for the entire field.

"As museums go, the new Brooklyn Children's Museum doesn't exactly conform to type. You go in through an old‐fashioned trolley car kiosk, walk down a ramped culvert of corrugated steel called a 'people tube,' and find yourself in a Rube Goldberg fantasyland of contraptions that seem designed to make busy, happy children even of grown‐ups."